There Are Cracks in Physics So Large a Quark Can’t Fit Through Them

Why you shouldn't feel bad that you don't understand Quantum Mechanics

Most people glaze over when they hear “quantum mechanics.” Fair enough—it’s a field famous for being impenetrable. Textbooks, equations, chalkboards full of Greek letters… it feels like a world reserved for geniuses in lab coats (or the last 2 chapters of your Freshman Physics textbook.)

But here’s the dirty little secret: the physicists don’t really understand it either. Not in the way we usually mean by “understand.” Richard Feynman admitted this explicitly. Because deep down, quantum theory is full of cracks—contradictions, paradoxes, and mysteries—so wide a quark couldn’t squeeze through them.

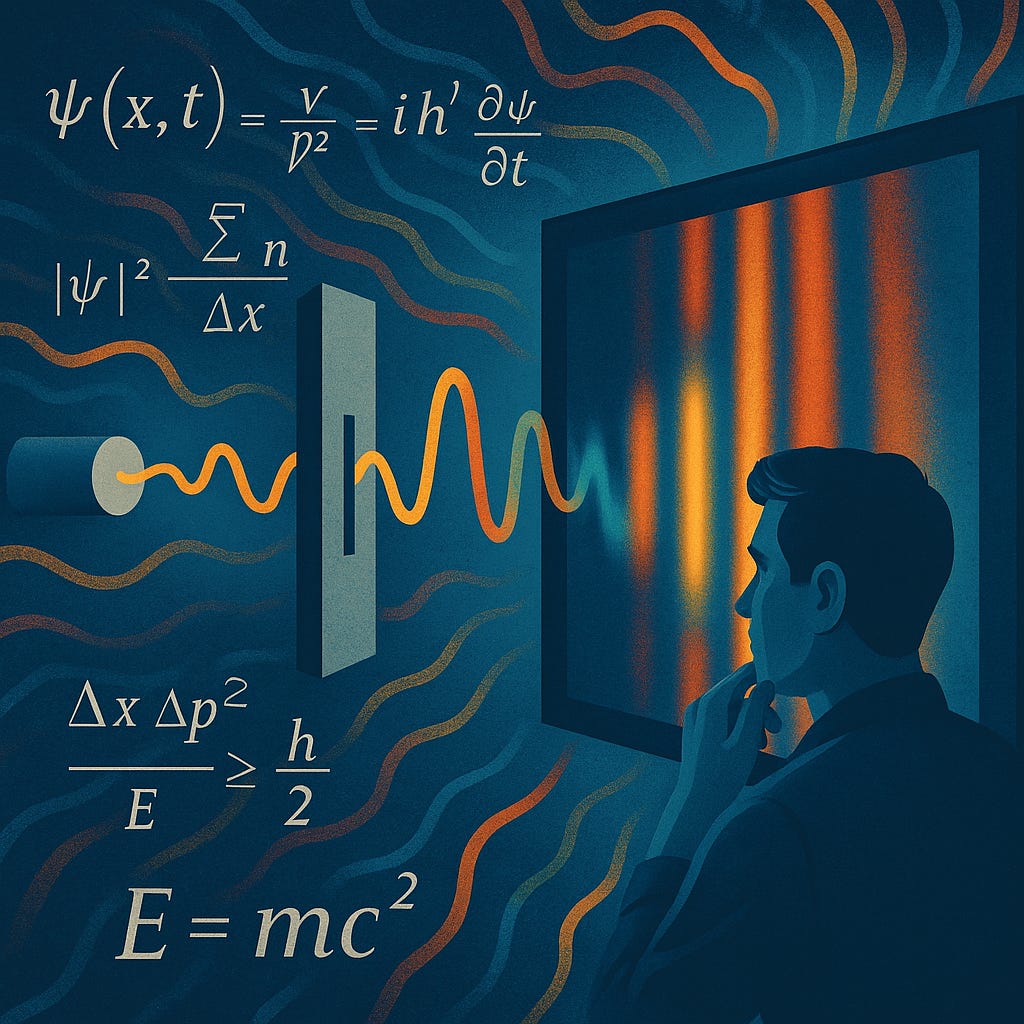

Take the double-slit experiment: shine electrons or photons through two slits, and they behave like waves, spreading into interference patterns. Shine them one at a time, and—still—they act like waves, as though each particle explores all possibilities simultaneously. But the moment you look, the wave collapses and the electron marches through like a tiny billiard ball. Are electrons shy? Do they change their behavior when observed? Are they having fun with us? That’s not how the rest of physics behaves—these behaviors crack the very dependability of reality. Especially when you consider what this behavior means.

Physicists know this. Richard Feynman once admitted the double-slit experiment contained “the only mystery” of quantum mechanics. Niels Bohr threw up his hands and declared that if you think you understand it, you don’t. And Einstein couldn’t let it go, railing against “spooky action at a distance” until his death. When the founders of physics confess their confusion, it tells us something: the cracks aren’t just in our ability to grasp them—they’re in the model itself.

And here’s the fun part: those cracks don’t close neatly under a matter-first worldview. That is, if the universe and reality are fundamentally based on matter, particles, things, stuff. If all reality is fundamentally particles and forces, then how do we explain behaviors that defy those very rules? This is what physics has been trying to figure out for a hundred years now (with no real progress, to be truthful.) Dark matter, dark energy, string theory, and so on. Temporary placeholders and band-aids for equations that simply don’t resolve.

Lets look at it another way. Under an information-first framework—the idea that reality’s substrate is not matter but information—these paradoxes become less strange. I daresay that they even start to make sense. An electron doesn’t “decide” which slit to take; it encodes probabilities across an informational field, collapsing into a single path only when measured. It essentially does not exist as matter until it is required, requested to do so. Observation isn’t a quirk. It’s a feature of the system. It’s almost as if consciousness itself is required to close the probability loop. But that’s a conversation for another day.

When I began corresponding with researchers like Hal Puthoff and Dean Radin, both emphasized in their own ways that treating anomalies as “noise” is a mistake. Dr. Radin, for instance, reminded me that psi effects, like quantum ones, make far more sense if you view them as informational constraints mediated by consciousness, not material causes bouncing off one another. The cracks are signals, pointing us toward a deeper substrate. Dr Puthoff called it a “medium.” When I discussed it with Rupert Sheldrake, he called it “form”. Whatever the terms we assign, it presents a new possibility. A novel framework to start hanging variables upon.

And maybe that’s the real takeaway: the cracks aren’t signs that physics is broken. They’re invitations. They tell us we’re brushing up against something deeper, something the equations hint at but can’t quite capture, if matter is the fundamental basis.

We’ve been patching the cracks for a century. Maybe it’s time to admit they’re not closing—because they’re not supposed to. Because they’re not cracks. They’re doorways.

That’s what my book It From Us: An Information-First Framework and the Purpose of Consciousness is about: how those cracks, those paradoxes, stop being absurdities once you flip the lens. Physics, biology, even religion—all suddenly rhyme when you treat information as the bedrock of reality.

So the next time you hear a physicist mumble about wave-particle duality or the collapse of the wave function, don’t feel left out. Smile. Because the truth is, none of us fully “get it.” Not yet. But if the cracks are this wide, something big is trying to shine through. And if It requires Us, like an electron seems to, then we’re part of the equation, not just the ones holding the chalk.

I really appreciate your perspective on the tangible world arising from information, and on logic preceding reality. It highlights an important recognition, that without coherence, even empirical observation wouldn’t be intelligible or possible. I’m curious about your thoughts on society’s heavy emphasis on empiricism, the notion that if something isn’t observable, it isn’t real. Given that coherence necessarily precedes empiricism, doesn’t this tendency end up undermining—even silencing—the very legitimacy of such discourse, relegating it to pseudoscience not because it lacks coherence, but simply because it lacks empiricism?